Chapter 2

Six cross-cutting lessons

Six cross-cutting lessons of the systemic nature of risk linked to the COVID-19 crisis

From the mangroves of West Bengal to the vast archipelago that makes up Indonesia, and from the bustling port city of Guayaquil, Ecuador, to the tropical shores of southern Togo, systemic risks from the COVID-19 pandemic have been exposed in stark human terms.

Millions of people who were already struggling to make ends meet, often working in the informal economy in agriculture, many also surviving below the poverty line, had to contend with a cascade of new risks that they could not possibly have foreseen as a result of COVID-19: joblessness, debt, civil and domestic violence, their children’s education derailed, and opportunities in general severely diminished. In many locations, women suffered disproportionately due to pre-existing gender biases in society, whether in employment patterns or in other ways.

Taken together, the human experiences in the five case studies that inform this report show what can be learned from places in the world that are not often in the headlines. Some of them may also be far from the majority of the most developed economies and population centres. They bring into sharp focus a very real challenge: how to better understand and manage the cascading, systemic risks that resulted from COVID-19 as it spread across boundaries and borders, touching almost everyone, globally.

The five locations, with their communities, were selected to provide a representation of the interconnected risks and COVID-19 impacts in various different settings. Our case study work in the Maritime region of Togo highlights the rural-urban and national-international interlinkages of COVID-19 in a regional Sub-Saharan context with high levels of poverty. The work in Guayaquil, Ecuador,provides insights into how COVID-19 overwhelmed a densely populated, overcrowded urban area.It also shows how a location’s dependence on global trade links creates and reinforces vulnerabilities. In the Sundarbans, India, we see how the concurrence of COVID-19 and natural hazards (in this case, a cyclone) creates cascading and systemic risks, as well as pointing to some worrying long-term effects. At Cox’s Bazar, in neighbouring Bangladesh, pre-existing social inequity in a fragile setting is the backdrop to understanding the pandemic’s effects on the world’s largest refugee camp, highlighting characteristics of highly dependent systems. Indonesia is the only one of our studies done on a national scale and highlights how COVID-19 led to interconnected challenges on multiple fronts: collapsing health systems, grave impacts on the economy and associated ripple effects on debt, poverty and inequalities, as well as on emergency response to other hazards that occurred amidst the pandemic.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to recognize that planetary and human systems are interdependent, and that risk knowledge systems need to become more flexible and open to different world-views.”

Jenty Kirsch-Wood, Head of Global Risk Analysis and Reporting, UNDRR

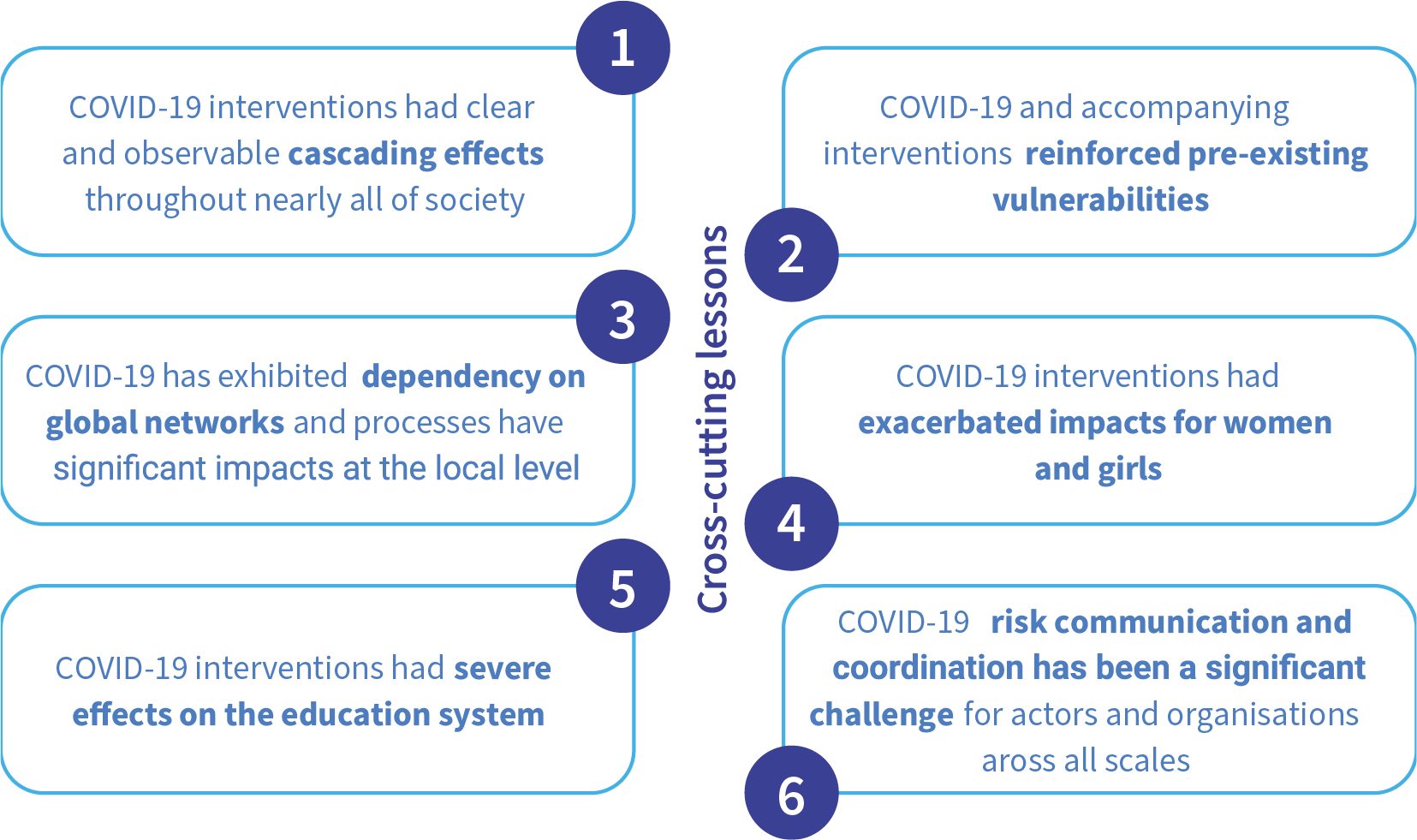

Six cross-cutting lessons that surfaced in all five locations may help to frame a response to the challenges thrown up in these and other locations.

A. Measures to combat COVID-19 have had cascading effects throughout society

One of the big cross-cutting themes emerging from the case studies is that nearly all the measures implemented to deal with COVID-19 had a domino, or cascading, effect through society and economies, impacting livelihoods, gender, education and political and social outcomes. Many of them led to further such effects.

Stay-at-home orders and social isolation resulted in sharp increases in mental health problems for many people. A general unwillingness to adhere to interventions led to widespread protests in Guayaquil, the Ecuadorian port city of 3 million inhabitants that experienced a devastating first wave of COVID-19. The reluctance of people to follow test and trace rules in Indonesia and Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, resulted in higher numbers of cases and a further weakening or even collapse of health-care systems.

Although the measures put in place to deal with the pandemic were obviously necessary to protect at-risk groups and avoid health systems becoming overwhelmed, the cascading effects of lockdowns made life much worse for many people. Take Togo, a sub-Saharan country with a large rural population and a significant informal economy. The Maritime region, located in the south, combines a large, remote and rural population with the country’s largest city and capital, Lomé. The arrival of COVID-19 in March 2020 prompted the government to implement lockdowns and curfews in cities to prevent Togo’s relatively weak health-care system becoming overwhelmed. While a catastrophic spread of the disease was averted in Togo, the consequences of the restrictions caused cascading effects in commerce, education and rural livelihoods. In Lomé, both the formal and informal economic sectors were badly hit, with widespread adverse effects on employment and livelihoods. Curfews were especially hard for people in the informal economy as a lot of trading occurs at night. The local experts consulted indicated that this had led to an increase in poverty across the region, affecting those most dependent on the informal economy.

Similar cascading effects were seen in South-East Asia’s most populous country, Indonesia. Government restrictions designed to tackle COVID-19 led to an immediate fall in economic growth, and as early as 2020, the government estimated that this could affect the Indonesian economy for at least the following decade. In response, the government introduced a massive fiscal stimulus package, mobilizing financial resources in part through cuts in state and regional budgets. As a result, multiple development projects, especially infrastructure and public facilities, had to bepostponed.The need for additional funds to fight the impacts of the pandemic has also led to a further increase in foreign debt and forced a revision of national development targets. The experts we consulted also confirmed that there was severe disruption to most economic sectors in Indonesia, notably in labour-intensive manufacturing of garments, leather and shoes, as well as in trade and service sectors. The biggest impact has been felt by small- and medium-sized enterprises and low value-added “micro businesses.” One year after the pandemic began, these enterprises' revenues had halved, compared with a decline of about 30 per cent for large companies, government figures show (BAPPENAS, 2021). According to experts consulted in workshops, this has led to further cascading impacts on livelihoods, employment, income and, in turn, poverty and household vulnerability. Unemployment hit 60 per cent, with higher rates in cities than in rural areas and for women compared to men. Bali’s tourism sector was particularly badly affected.

B. COVID-19 has reinforced pre-existing vulnerabilities in society

A second cross-cutting theme is that COVID-19 reinforces pre-existing vulnerabilities; that is, it makes life even more difficult for people already facing challenging circumstances. This worsens inequality and injustice throughout society. As we saw in the Maritime region of Togo, the closure of night markets and the reduction in demand for food products saw a loss of income for those already living in poverty.

We can also see this effect in Guayaquil, Ecuador, where families already living in overcrowded housing suffered more from stay-at-home orders than those in more favourable living situations. The city’s health-care system reached a tipping point in a matter of weeks after the first case was detected in February 2020, resulting in a high number of corpses being left unattended in hospitals and care homes, as well as on the streets. The images of bodies accumulating in the streets that circulated in the global media were among the first to show what happened when COVID-19 arrived in densely populated urban areas. By March, the city had an excess mortality rate five times that of the same month in 2019 (Cabrera and Kurmanaev, 2020) and the highest COVID-19 mortality rate of any Latin American city (WHO, 2021). Not only had many people been working in the informal economy in significant poverty, already vulnerable, but as was noted in the workshops, many had to deal with the added problem of living in overcrowded housing. Indeed, Guayaquil has the most overcrowded housing of any city in Ecuador. Space constraints made social distancing over weeks and months all but impossible for many.

Pre-existing vulnerabilities were reinforced in other ways. Returning to the case of Togo, agricultural production was also severely compromised during the crisis. Pandemic restrictions resulted in an uptick in migration from rural to urban areas, involving young people moving to Lomé in particular. Not only did this add to pre-existing labour shortages in agricultural regions, but it was also unhelpful given that the soil in these areas was already suffering from decades-long overexploitation and was therefore struggling to produce enough to sustain the region’s growing population. Our workshops revealed that this resulted in a reinforcing feedback loop of reduced agricultural production, in turn leading to price inflation, ultimately worsening food insecurity for poor households. This, combined with certain restrictions on cross-border commerce, even contributed to a rise in illegal smuggling across the border with neighbouring Benin.

Finally, the experience of the elderly and people with disabilities in the largest refugee camp in the world, at Cox’s Bazar in the southernmost district of Bangladesh, highlighted the reinforcement of pre-existing vulnerabilities in still further ways. Cox’s Bazar is home to almost 900,000 Rohingya people from about 190,000 families (UNHCR, 2021). Due to the centralization of servicesat the campsand other factors, food packages were distributed only at specific locations on a monthly basis, which in turn made packages heavier. This disproportionately affected people with disabilities and the elderly,who struggled to receive such food aid and could not afford to pay others to deliver them.

C. Dependence on global networks has had a big impact at the local level

In a world that has steadily globalized in recent decades, it is no surprise to find that certain locations are highly dependent on global networks.

Port cities such as Rotterdam, Singapore and Karachi are good examples. Another is our case study of Guayaquil, Ecuador, which vividly illustrates what happens when global economic dependency is disrupted by a pandemic. Other case studies highlight the impact that is felt when disruption to global trade filters through to the informal sector in a local economy, such as in Lomé, Togo, where many people worked in night markets and had little job security. In the Sundarbans, India, disruption in global and national supply chains and networks resulted in the sudden collapse of tourism-based livelihoods and a lack of markets for local products (particularly seafood).

Global trade has significant effects at the local level, as was evident in the city of Guayaquil. The city’s port handles almost all of Ecuador’s imports and half of its exports, making it the country’s main trade centre. The sharp slowdown in global trade that was sparked by COVID-19 devastated the city’s economy, causing widespread job losses, pushing many further into poverty.

International collaboration and support are of course vital for effective risk management, especially at times of disaster. This is where another aspect of Guayaquil’s — and Ecuador’s — dependence on global networks emerged as an issue. In the workshops, health experts pointed out that state and municipal authorities were heavily reliant on the flow of information from global sources for how policy should be applied at the local level. However, in the initial phases of the pandemic, even international bodies like WHO were unable to provide clear guidance, resulting in the issuance of unclear information, which in turn resulted in slower uptake of health policy measures and ambiguous communication from the Ecuadorian government, particularly on mask usage. This was one factor that contributed to the spread of misinformation throughout digital social networks.

D. Measures to combat the pandemic have had distinct effects on women and girls

Increased exposure to COVID-19 through work; more manual and domestic labour; an increase in domestic violence; and even involvement in child marriages: all of these were experienced by women and girls in many of the locations in our case studies. This reinforces how gender is a key factor in risks associated with crises and how their impacts are felt disproportionately by women and girls.

The plight of women and girls in the Sundarbans, a vast mangrove delta in India’s West Bengal, is a case in point. This archipelago of islands is part of the largest contiguous mangrove forest in the world, home to millions of people, where 43.5 per cent of households live below the povertyline and more than 87 per cent experiencefood shortages (Ghosh, 2012; HDRCC Development & Planning Department Government of West Bengal, 2009; 2010).

To contain the spread of COVID-19, the government in New Delhi implemented a countrywide lockdown in March 2020. Barely a month later, a severe cyclone named Amphan made landfall in the region.

The impact of two hazards occurring simultaneously was a double burden for people in the Sundarbans, India, many of whom depend on natural resources for livelihoods generated from fishing, crab harvesting, beekeeping and other agricultural pursuits. COVID-19 restrictions naturally made it hard for people to carry on accessing these natural resources to serve a market that had all but collapsed in any case. One result of the economic distress this caused was an increase in the incidence of forced marriage among underage girls, including the sale of daughters by parents, in the aftermath of the cyclone in the case study area. In addition, many women had to work extra hours in the fields as a result of having to fill in for hired workers who were laid off due to the effects of COVID-19 on the labour market. The full impact of this may only become apparent in the longer term, experts in the consultation workshops argued. Making matters worse for women, the cyclone caused flooding and damage to infrastructure, restricting access to safe drinking water. This forced many women to travel further to work and in some cases go through “neck-deep water” to fetch safe drinking water (Chattopadhyay, 2020).

Women were disproportionately affected by the cascading effects of COVID-19 elsewhere, too. In the Maritime region of Togo and in Indonesia, women were more exposed to loss of livelihood and economic opportunities given that they were more likely to be working in areas involving relatively higher interaction with other people — and thus greater exposure to the virus — such as markets, hair salons and restaurants. And in Guayaquil, Ecuador, the Sundarbans, India, and Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, experts consulted during workshops noted that women and girls tended to work more than usual in manual labour throughout the pandemic to compensate for family financial losses.

In all cases there were increased instances reported of domestic and gender-based violence. In Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, and Guayaquil, Ecuador, it was noted in workshops that this is likely to be due to a combination of lost livelihood opportunities and stay-at-home orders. On top of this, women were found to be taking the lead in homeschooling, further widening a gender pay-and-time gap. In Indonesia, it was noted that the focus on COVID-19 reduced provision of maternal health-care facilities, resulting in an increase in deaths during childbirth.

BOX 1: Women hold up half the sky yet have been disproportionately affected by pandemic-related risks

Disasters amplify pre-existing inequalities. This also holds true for gender inequalities. Women, girls and gender-diverse people have experienced disproportionate indirect health impacts, as well as a multitude of cascading effects. Those who face intersectional inequalities due to their income, race, geographic location, age, disability, migration or health status have been particularly affected. These impacts have challenged the equitable and effective distribution of health and social care, restricted mobility, deepened inequalities and shifted the priorities of public and private institutions.

Much of this was brought into stark relief in our case studies. Increases in gender-based and domestic violence were documented in all of the cases.

For example, an overburdened health-care system in Indonesia has resulted in a lack of access to maternal and reproductive services. In Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, opportunities that girls had for education decreased due to school closures, contributing to, among other factors, increased incidences of child marriage.

Moreover, social protection schemes rolled out to protect against the adverse effects of COVID-19 have been implemented insensitively when it comes to gender. Only 23 per cent of all social protection measures introduced have either targeted women’s economic security specifically or accounted for unpaid child and elder care (UNDP & UN Women, 2000). Women and girls in communities already reeling from institutionalized poverty, racism and other forms of discrimination are particularly at risk.

Why do we see these impacts? In part because women are far more likely to be working in front-line sectors affected by the pandemic. As much as 70 per cent of the global health-care workforce is staffed by women. This figure rises to 90 per cent if social care is included. Women are more likely to work in key service sectors — supermarkets, pharmacies, cleaning — that have been essential to maintaining daily life throughout the pandemic (Lotta and others, 2021).

However, throughout the pandemic there have also been countless instances of exemplary public and private leadership, innovation and mobilization led by women, girls and gender-diverse people. Furthermore, many female heads of government have been recognized globally for their effectiveness in managing the pandemic.

Examples from our case studies include the female volunteer groups in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, that have been providing advice on responsible hygiene, social distancing and medical treatment. Similarly, in the Maritime region of Togo, the spreading of information about hygiene practices to reduce contagion was supported by the Club des Mères (mothers’ clubs). Established and supported by Togolese Red Cross and active since 2012, these groups of local women, particularly in remote areas, receive training on appropriate hygiene practices with a mandate to raise awareness about good hygiene and health practices and take this knowledge back to their remote communities. In the Sundarbans in India, women’s self-help groups and female-led cooperatives have provided employment and loans that have helped women to repair cyclone-damaged houses.

It has been noted that the leadership styles of women have been more collective, collaborative and integrated multiple perspectives (UN Women, 2021), which has been necessary when responding to a highly dynamic and uncertain disaster. This trend can also be seen from female leaders at more local levels, as witnessed in some of our case studies.

All of this serves to underscore the importance of the role of diversity, equality and social justice in response to and recovery from the pandemic, as well as for disaster risk reduction. It also points to the need for gender-specific measures to offset the widening gender-equality gap that the pandemic has intensified.

E. Education suffered, and the full effects may only become apparent over time

Education was another aspect of daily life that suffered as a result of COVID-19 restrictions, as many children and parents will know. Yet the pandemic had particularly severe effects on the educational opportunities of children in many of our six case study locations. While these effects are likely to have reinforced underlying inequalities and exacerbated pre-existing vulnerabilities, many of them will only fully emerge in the future, demonstrating the delayed cause-effect nature of cascading and systemic risks.

In particular, the movement to online learning was an issue in the Maritime region of Togo, the Sundarbans, India, and Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, due to limited digital infrastructure in these locations. There was a distinct “digital gap” in all cases, meaning that people either could not access the Internet, or did not have the equipment required to access online learning. In Cox’s Bazar in particular, this meant that there was no alternative to in-person schooling, resulting in a complete shutdown of educational facilities. Additionally, in the Sundarbans, unstable Internet connectivity in remote regions compounded poverty in preventing families from paying for tools toaccess online education. When this was combined with the effects of Cyclone Amphan, the disruption to education became conspicuous. The cyclone also had long-term effects, particularly forgirls, with a spike in child marriage reported by the workshops and consultations.

Instances of children dropping out of school increased significantly across the board in the case studies, leading in turn to an increase in reported cases of child labour in Guayaquil, Ecuador, the Sundarbans, India, and Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh

BOX 2: Cascading effects: Two lessons from education in Germany

1. Socioeconomic background matters to educational outcomes

Systemic and cascading risks are not only an issue in low- and middle-income countries.Germany is one of the most economically developed countries in the world. That means it ought to have been able to cope relatively better than other countries in dealing with the impacts of COVID-19, given its significant financial resources and good health infrastructure.

However, a different, more mixed, picture emerges when we look at educational outcomes as a result of the impact of the pandemic, which has forced most education online and much of the population into “homeschooling” mode. Certain groups of children and parents have been at a disadvantage.

The quality of a home-learning environment depends to a large extent on the educational support given by parents, which is linked to their socioeconomic backgrounds. Yet, research found that parents with lower levels of education, as well as migrational backgrounds, have faced greater difficulty supporting their children in homeschooling (Wolters and others, 2020; Rude, 2020). In low-income groups, parents were often less able to work from home and, to avoid financial losses, were more likely to leave their children unsupervised (Zoch and others, 2020).

In addition, children from families with lower incomes, migrational and non-academic backgrounds have experienced fewer joint learning formats, such as video conferences, providing direct contact between teachers and children, which was seen to be important to facilitate the learning-from-home process (Blaeschke & Freitag, 2021; Huebener and others, 2020; Langmeyer and others, 2020). Lower-performing children were more likely to be in a less advantageous home learning environment (Geis-Thöne, 2020; Huebener & Schmitz, 2020).

These results suggest that the structural shift to online learning has had a reinforcing feedback effect for underperforming children that performance gaps may well widen over time as a result of the pandemic. Worse, if the educational losses experienced by these groups are not compensated for, there is a risk that children who were already disadvantaged because of their socioeconomic background end up having fewer educational opportunities and, therefore, fewer opportunities in the labour market.

Looking at what happened in Germany, the sudden closure of schools as part of lockdowns could thus lead to long-term consequences that only become apparent after some time. It may be that existing social inequalities in education and income in Germany will therefore persist, or even increase, over time as a result of COVID-19.

2. Women have been disproportionately disadvantaged

Women have been in key respects more affected than men by the pandemic.

Working parents have been confronted with the sudden challenge of organizing childcare or homeschooling and their work at the same time. Yet their ability to deal with this has depended on their professional situations, as well as on family arrangements. Couples that could divide family responsibilities have been less affected than single parents, who have experienced both a greater organizational challenge and more of a psychological burden.

Single parent households have found this particularly challenging. But so did women, who have been disproportionately affected by the challenges thrown up by school closures. Due to the pre-existing gender pay gap in Germany, women have more likely to compensate in their work for homeschooling duties. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that women were more likely to work in essential services jobs, many of which do not offer the possibility of working remotely to facilitate childcare duties (Kohlrausch & Zucco, 2020; Wersig, 2020).

The combination of fewer working hours and economic slowdown points to a risk that the gender pay gap may worsen in the long term, and there is a risk that women face the possibility that they may not be able to automatically return to pre-pandemic working patterns. This and other factors mean that women have been, and are likely in the future to be, confronted with more financial difficulties, further reinforcing underlying inequalities and highlighting the importance of protecting the education system in times of crisis.

F. Risk communication and coordination were significant challenges for authorities at all levels

Dealing with a global pandemic obviously requires effective coordination and communication among key actors, from national governments and multilateral non-governmental organizations (NGOs) down to local authorities. However, in all our case studies, decision makers across the spectrum dropped the ball at certain times when it came to communication of the risks involved, as well as in coordinating responses to the pandemic. This was particularly evident in the early stages of the pandemic due to the reality that COVID-19 was a novel, highly uncertain and highly dynamic hazard. As we saw earlier, slow uptake of health policy measures by the Ecuadorian government was in part due to patchy messaging from WHO.

Consultations with experts in the Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, case underlined the importance of involving religious or community leaders in effective risk communication to prevent the spread of misinformation. In the Sundarbans, India, government health measures resulted in the mass movement to rural areas of migrant workers from densely populated areas with high case numbers.

In Indonesia, a combination of limited knowledge of the disease, lack of coordinated response and inconsistent policy messages from the national government and regional governments contributed to a low willingness of the population to test and trace. These factors, combined with insufficient preparedness of the health-care system, resulted in the country having the fourth highest fatality rate of health-care staff globally as of mid-September 2020. In the workshops, experts highlighted this as an example of a vicious cyclethat created additional challenges in the fight against the pandemic.

Management decisions taken at the local level will invariably depend on what signals and data are being received from authorities at the national and, in turn, global level. This was seen in the city of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Poor coordination from the Ecuadorian national government resulted in siloed communication, which hindered the ability of public institutions to set up early-detection, warning and monitoring systems, such as contact-tracing and testing. In addition, there were not enough laboratories to process tests in Ecuador, resulting in a slow turnaround of test results, which were critically needed in the city of Guayaquil during the first weeks of the pandemic. Another finding stressed by health experts in the workshops concerned the response of the Ecuadorian government being significantly influenced by uncoordinated communication at the global scale. As in many low-income and middle-income settings, international support and guidance are imperative components for comprehensive risk management, especially in times of disaster. Coordination and communication issues from WHO, such as confusing guidance on wearing masks at the start of the pandemic, resulted in the output of unclear information, which prompted a slower uptake of protocols and ambiguous communication from the Ecuadorian government. Workshop participants noted that this was one of the factors that contributed to the spreading of misinformation through social media. Ultimately, the response from the Guayaquil city municipality and the Ecuadorian government's public institutions fell short due in part to lack of an integrated, cross-sectoral response that concerned flows of information from the global to local levels.

BOX 3: How COVID-19 affected progress on UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

1. The link between COVID-19 and the SDGs

The pandemic and its consequences are jeopardizing progress towards the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which covers developmental issues such as reducing poverty, tackling food insecurity, homelessness and access to clean water. We have tracked the effects of the pandemic on the SDGs observed in our case studies.

Effects observed in our case studies include:

- No poverty (SDG1): More people were pushed into poverty (Guayaquil, Sundarbans, Indonesia and Maritime region of Togo). People in slums and rural areas (Maritime region of Togo) as well as informal workers(Guayaquil, Indonesia and Maritime region of Togo) were particularly affected.

- Zero hunger (SDG2): The restriction of mobility through border closures and lockdowns limited food supply, raising food prices (Indonesia and Maritime region of Togo). This left people with few means to survive, resulting in widespread food insecurity (Maritime region of Togo).

- Good health and well-being (SDG3): In the Maritime region of Togo, though the fear of infections has prevented people from using health services, the scarcity of health workers contributed to the risk of total collapse of the health system. Stress and mental health became a bigger problem due to increased economic uncertainties (Sundarbans and Guayaquil), and co-morbidity increased in Indonesia due to reduced availability of, and access to, reproductive and maternal health care.

- Quality education (SDG4): Schools were closed for an extended period, leading to school dropouts (Cox’s Bazar, Guayaquil and Maritime region of Togo). Poor families were affected by the switch to online learning due to a lack of adequate infrastructure (Sundarbans and Indonesia).

- Gender equality (SDG5): The closure of schools correlated with an increase in forced marriages (Cox’s Bazar and Sundarbans) and child labour (Cox’s Bazar), and girls were ten times more at risk of dropping out of school than boys due partly to a rise in early marriage (Indonesia).

- Clean water and sanitation (SDG6): Water consumption increased (Indonesia). Floods and landslides contributed to water contamination (Cox’s Bazar and Guayaquil).

- Decent work and economic growth (SDG8): Informal workers lost their jobs and incomes (Sundarbans, Indonesia, Maritime region of Togo and Guayaquil). In Togo, employees in the informal sector, as well as vendors, were forced to close due to curfews. The closure of schools contributed to an increase in child labour (Sundurbans) as well as involvement of children in illegal activities (Cox’s Bazar).

- Reduced inequalities (SDG10): In India, the return of migrants was accompanied by an increase in inequality due to them being treated differently (Sundarbans). Relief distribution suffered due to corruption (Sundarbans).

- Sustainable cities and communities (SDG11): Urban homelessness increased (Indonesia).

- Peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG16): Insufficient governance has led to increased corruption and conflict (Sundarbans and Guayaquil).

2. “Building back better” and commitment to the SDGs

As we recover from the pandemic, it is necessary to strengthen the commitment to achieving the SDGs. However, this should be done not just by focusing on reducing possible future hazards but also by acting on people’s and societies' vulnerabilities while leaving no one behind. With lower social vulnerability, healthier ecosystems and more resilient economies, the impacts of COVID-19 would have likely been less severe. In addition, more sustainable and equitable city planning would help provide adequate housing and places for quarantine, facilitating social cohesion and trust in local communities. The SDGs are an established, globally applicable framework that can incorporate an interconnected systemic perspective. This makes them a highly suitable framework for systemic recovery from COVID-19 impacts, offering a clear way forward.

Get more into detail:

CONTACT

UN Campus

Platz der Vereinten Nationen 1

D–53113 Bonn

+ 49-288-815-0200

+ 49-288-815-0299

2022 © copyrights UNU-EHS